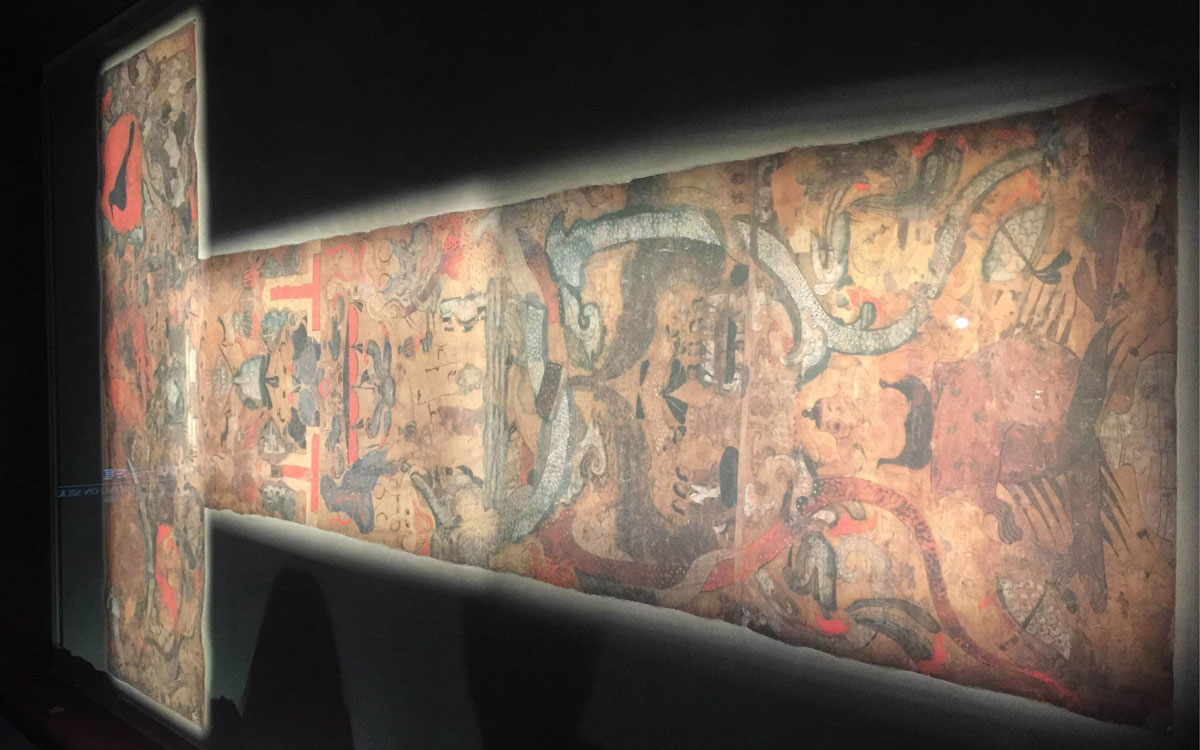

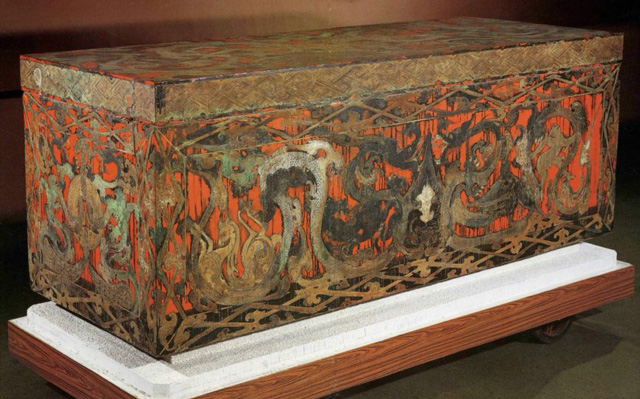

The 馬王堆漢墓/马王堆汉墓/ma3 wang2 dui1/Mawangdui Han tomb is one of the most famous Han dynasty archaeological sites in China. Located in Mawangdui, Changsha, this elaborate tomb was found in 1968 and excavated in 1972 to reveal the remains of an incredibly well-preserved noblewoman that we now know was the wife to the Marquis of Dai in the Han Dynasty Kingdom of Changsha, Li Dai. A multilayered burial site containing furniture, food, art, accessories, and other belongings, the tomb contained her personal seal, which was found with the name 辛追/辛追/xin1 zhui1/Xin Zhui engraved in it; thus we know her as 辛追夫人/新追夫人/xin1 zhui1 fu1 ren2/Lady Xinzhui.

wax reconstruction of what Lady Xinzhui would've looked like in her youth

(A quick disclaimer—this series of articles is a result of my own research. I’m not a trained historian or archaeologist, I’m an inexperienced student with an interest in hanfu and chinese history. I don’t have a works cited page for these (though I can point you towards some of the resources I used off the top of my head if you really want them), and I didn’t spend a long time verifying my sources beyond checking with multiple sources to make sure the information was consistent, because frankly I don’t have the time to do that. All articles will come with this disclaimer, so please, please understand that I’m doing my best with what I have and forgive me for any mistakes!!!)

Lady Xinzhui would have lived in the Western Han Dynasty, where similar to what we know about Egyptian pyramids and burial rites, it was believed that a person needed to be buried with their belongings and possessions so that they could take them with them into the afterlife. Her mummy was also incredibly well preserved, with eyelashes and elastic skin and muscles that were still intact enough to move her joints, and an autopsy revealed that she would’ve died at around 50 years old from something like a heart attack thousands of years ago at around 168 BCE. She was buried with close to a hundred pieces of clothing, some of which are still on display in various museums today. Some of the oldest types of hanfu we know about were referenced off of Lady Xinzhui’s extravagant wardrobe, of which there were one skirt and a dozen robes. Let’s go over some of the most famous clothing relics we found in her tomb.

素紗襌衣/素纱襌衫衣/su4 sha1 dan1 yi1/Susha Danyi

An excellent example of the incredible textile technology developed in ancient China, the susha danyi is a feat of the Han dynasty silk industry that’s earned quite a name for itself over the years. This full length robe follows the general shape of hanfu that we would call a 直裾袍/直裾袍/zhi2 ju1 pao2/straight hem robe today, a full body robe with a classic crossed collar, right over left, and a straight uncurved hem that circles the wearer’s body at the same height all around. We would classify this kind of clothing as 深衣/深衣/shen1 yi1/deep clothing, or full-body clothing, what we would usually call a robe, as it covers the full body and would probably end up with the hem falling somewhere around the lower leg or ankles.

The sleeves are mostly straight with no curvature, though still very wide, and feature cuffs of contrasting darker color fabric as decoration, similar to the contrasting taping around the collar area. The crossed collar, right over left as usual, is made fairly wide, which is more common for clothing meant to be worn on the outer layers to allow for the collars of the layers underneath to show through.

What’s really remarkable about this piece of clothing is its material. Made of a single layer of pure natural silk, the entire garment is so thin and light that it weighs in at about 49 grams. To put that in perspective, that’s about the weight of ten quarters. The whole thing can be folded up and stuffed into a matchbox, and the silk allows more than 75% of light to pass through. The silk is completely undyed or colored by any other means, giving it the name 素紗/素紗/su4 sha1/plain gauze, since the material is gauzy and true to its original form with no other processes for decoration, and the single layer constitutes the second part of the name 襌衣/襌衣/dan1 yi1/single cloth. This is an example of a level of lightness that today’s looms would never be able to achieve—and it’s so tightly woven that the thin strands of silk haven’t unraveled in over 2000 years of burial.

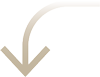

朱红菱纹罗丝绵袍/朱紅菱紋羅絲綿袍/zhu1 hong2 ling2 wen2 luo1 si1 mian2 pao2/Red Diamond-Patterned Thick Silk Robe

One of the most classic examples of a 曲裾袍/曲裾袍/qv1 jv1 pao2/curved hem robe, the red diamond-patterned robe is what a lot of hanfu retailers and designers reference for the quju shape. The curved hem refers to the frontal outer hem of the robe that curves up the front of the wearer’s body from the wearer’s left to their right, spiraling up the lower body to create a wavy shape. Particularly popular in the Qin and Han dynasties as unisex wear and gradually evolving to be only feminine, our Lady Xinzhui’s wardrobe contained quite a few of these!

Similar to the straight-hem robe, this robe also has a crossed collar, left over right as usual, though the back of the collar wraps around the neck fairly generously compared to the outer-worn susha danyi. These sleeves are a less commonly seen sleeve shape known as 垂胡袖/垂胡袖/chui2 hu2 xiu4/drooping sleeves, usually only see in Qin/Han dynasty clothing—by the time the big three dynasties, Tang, Ming and Song rolled around, this sleeve shape wasn’t very popular anymore. Drooping sleeves characteristically curve down slightly from the root of the sleeve then round upwards to a narrow cuff—the initial curve down on this particular robe isn’t very obvious, but the narrow cuff is clearly there. Contrasting color fabric widely tapes the cuffs, collar, and hem; the robe is lined.

weaving pattern of the red robe

This robe is made of silk, dyed a single bright vermillion color, but what’s remarkable about this fabric is the way it was woven. The diamond-shaped pattern on the fabric requires incredibly sophisticated weaving technology to create the small square holes in the middle while still keeping the threads tightly spun together: with more than 330 warp threads and more than 200 weft threads in one cycle, it’s too complicated for a single jacquard loom to accomplish, requiring something twisting the warp and a loom working together with two operators. In a time when there were no computers or printers to repeat patterns of a loom quickly, this would all have to be mapped out by hand.

絹地“長壽繡”絲綿袍/绢地“长寿绣”丝绵袍/juan4 di0 chang2 shou4 xiu4 si1 mian2 pao2/Changshou Embroidered Thick Silk Robe

Another curved-hem robe, the Changshou embroidered robe has some of the most complicated patterning on it out of the robes found in the Mawangdui Han tomb, mainly because it employs embroidery.

Along with the rest of the robes so far, this robe has a crossed collar, left over right, similar to the previous curved-hem robe, and also drooping sleeves. The cuffs, collar, and hem are taped with two different colors of fabrics, one darker and one lighter than the main fabric, the darker color being wider than the light color. Historians suspect that this piece of clothing was buried with Lady Xinzhui because it was likely one of her favorite robes.

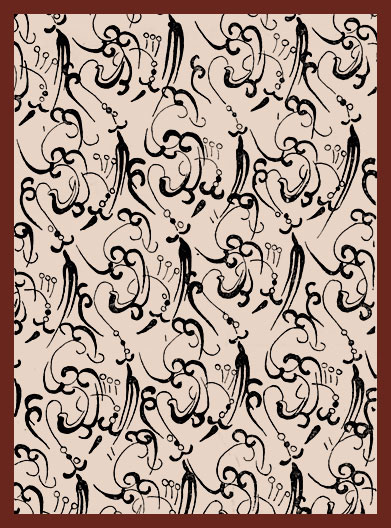

embroidery pattern of the robe

And for good reason—the patterning on this robe is beautiful. Resembling tumbling clouds and leaves, the embroidered surface of the robe’s body is decorated with silk threads dyed vermillion, dark green, yellow, and golden. A lot of the colors are faded by now, but you can tell how vibrant the pattern would have been two thousand years ago when Lady Xinzhui wore this piece in her daily life. The inside of the robe is lined.

羅地“信期繡”絲綿袍/罗地“信期绣”丝绵袍/luo2 di0 xin4 qi2 xiu4 si1 mian2 pao2/Xinqi Embroidery Gauze Silk Robe

The last of the curved-hem robes we’ll be talking about today, the tea-colored Xinqi embroidery robe displays a rhomboid pattern pretty similar to the one from the red diamond-patterned robe, but with several contrasting colors, not just one vermillion color.

Still with a crossed collar and drooping sleeves, the taped edges on the collar, sleeve cuffs and hem are also double-layered here with two different colors of thicker fabric, the same kind of thin but tough silk used in the red diamond patterned robe. The curving on the sleeves is less prominent than that of the previous two drooping sleeve shapes, but the overall width of them are fairly wide and still curve up slightly to the sleeve cuff.

pattern on the robe

Lined with thicker fabric, this would’ve been part of Lady Xinzhui’s winter wardrobe, thicker to protect her against the winter winds. Several other relics unearthed from her tomb are made of the same kind of Xinqi embroidery fabric, with 19 in total, though not all of them necessarily clothing—this robe is one of the most well-preserved. The design includes rhomboid shapes of reddish brown, vermillion, and dark green color, though the colors have faded with time.

印花敷彩紗絲綿袍/印花敷彩纱丝绵袍/yin4 hua1 fu1 cai3 sha1 si1 mian2 pao2/Printed Multicolor Silk Robe

Moving away from curved-hem robes once again, let’s look at one of the classic examples of straight-hem robes instead. Similar to the shape of the susha danyi, this type of robe has a straight hem that wraps levelly around the wearer’s body at the hem, not curving up as in the case of the curved-hem robe.

This robe also has a crossed collar and drooping sleeves with a pretty clear curvature. Unlike the quju shenyi (curved hem shenyi), the zhiju robe doesn’t wrap tightly around the lower half of the body in the same way that the curved-hem robe does—while the extra fabric of the curved-hem robe is triangular in shape, allowing the hem to curve up the body as it’s tightly wrapped around the legs, the rectangular shape of the zhiju robe’s extra fabric is tied loosely around the lower body, allowing for a more generous fit, though the overall length of the robe seems to be shorter. The hem, cuffs, and collar are taped with a single wide light-colored border.

printed/hand painted pattern

Like the other robes unearthed from this tomb, this robe is made of silk gauze on the outside, lined on the inside. The pattern on the outside of this robe isn’t woven, dyed, or embroidered like the other robes, though; it’s printed—similar to the way that patterns are printed on today’s clothing. You can see a repeating floral pattern throughout the robe’s main body fabric, with imperfections in each variation of the pattern, suggesting that the pigment was likely hand-painted onto the fabric. This kind of fabric decoration is painstaking and difficult to upkeep, hence why we don’t see it very often. Two other robes of similar shape and measurement were unearthed from the tomb with the same kind of multicolored painted fabric.

絹裙/绢裙/juan4 qun2/Thick Silk Skirt

This skirt is the only skirt in the collection—Han dynasty people really liked their robes! Constructed with four piece of fabric, it’d usually be worn under a robe as an underlayer for warmth or to line the skin against some rougher fabrics worn on the outside. Made of a thick silk similar to some of the robes from before, this is a weave of silk that’s relatively thick but still loosely woven. This skirt is dyed a red-purple color, though the color has mostly faded back to red. Worn on the body, it isn’t long enough to be seen below outer layers of zhiju or quju robes.

Constructed out of four trapezoidal pieces of fabric, we could refer to this skirt as a 四破裙/四破裙/si4 po4 qun2/four-piece skirt, in the same family of fabrics as the eight, twelve, and sixteen poqun, which are all made of trapezoidal piece of fabric stitched together. The effect is a circle skirt-like garment that hangs down naturally when tied at the waist. The skirt head unites the four pieces, and is extended for the skirt ties. This is a very familiar silhouette that we’ve seen in modern hanfu a lot, though more sophisticated types of poqun popped up as the most fashionable skirts later on in the Wei and Jin dynasties—for now this is only an underlayer.

That’s all I’ve got for now—hope you enjoy what you’ve seen so far! These articles really do take me a long time to research for, especially since everything is in kind of technical terms on Chinese archaeology and history sites, so keep an eye out for the next archaeological dig site analysis in the next few weeks. My sources this time were mostly from the Hunnan Museum’s webpage (all of the listed pieces are on display there) as well as some other Baidu, Baike and Sohu articles online, you can try to look for those yourself if you want more information. Let me know what you liked reading about and what you’d like to see more written about!

More about Hanfu Unearthed Series:

About the silk skirt, is it originally shaped like that? Like, it's not a product of stretch of age or moisture or something else?

There's gonna be some aging going on there—it has been a couple thousand years—but in terms of the trapezoidal pieces, that should be correct, cross-referenced with writings and art. Given the construction it should come out with a slightly curved skirt head and hem, but it'd probably be more even. I don't doubt that there's some shrinkage and wrinkling going on in the picture, though.

Translucency is definitely no excuse to weave loosely 😆

Hahaha loose might not be the right word, gauze is woven in a pattern kinda like the leno weave, where it leaves some spaces in between the fibers, not sure if that came across right or not

Thanks! Great article😍

***UPDATE ON FABRICS SINCE I WASN'T SURE HOW TO TRANSLATE THEM AT FIRST!!! - 絹/绢/juan4/Juan is tabby silk, silk woven in a plain weave that's also called taffeta weave. - 罗/罗/luo2/Luo is silk gauze, woven with stranded warps, typically very loose and thin.

OMG. Okay. Thank you.

Your writing is so nice and clear and well explained! It’s really cool how advanced their weaving tech was back then, so much so that we couldn’t even replicate it nowadays :O For future article suggestions, I guess excavations from a nice wide selection of time periods and maybe imperial family tombs? 👀👀

Thank you!!!! Yeah, I'll try to cover 1-3 tombs from each time period!