So now that you’ve learned about all these pieces separately, we arrive at the question: how do we put all of these pieces together? Let’s go over some ways these are usually put together, how to refer to them, and other details that might not have been covered in previous articles.

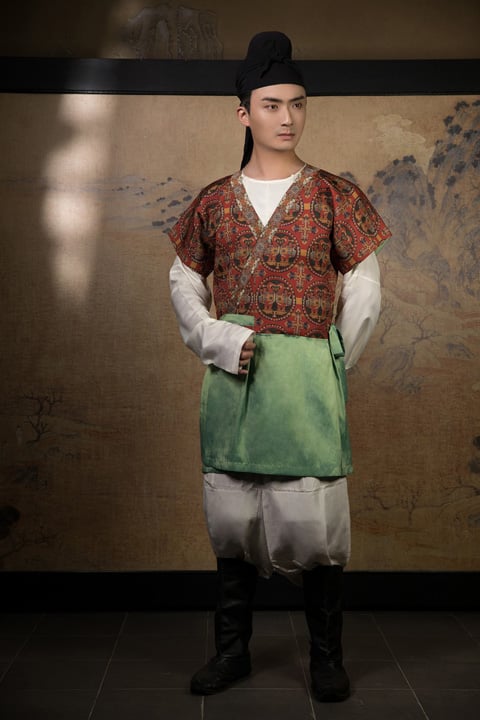

Body, sleeves, collar: these are the main three things that we use to distinguish types of hanfu. In naming conventions, we usually refer to a piece in the order of collar-sleeve-body. Take a look at this image:

What body type, sleeve type, and collar type is it? Well, I’ll tell you first that this is a Shan, meaning that it’s a single-layered top or robe shorter than the knees with no yao lan. Take a look at the sleeves—do they curve or change in diameter at all? Yes, they seem to narrow in a striaght line from the root of the sleeve to the cuff, meaning this is a feijixiu design, or airplane sleeve. The collar’s shape is pretty obviously parallel, or duijin, since the two sides come straight down and don’t touch. Well then, we can refer to this as a duijin feijixiu shan: a parallel collar, airplane sleeved shan. These are very common in Song dynasty sets and are often just referred to as feijixiu, or feijixiu duanshan, since it's the most common combination of conditions for feijixiu to appear in.

Some combinations have their own names too, as you’ve definitely seen! A quling ru, curved collar ru top, is often called a 晉襦/晋襦/jin4 ru3/Jin dynasty ru. Sometimes names can be given to pieces based on how they’re usually worn, too: a half-sleeve duijin ao is often a 披襖/披袄/pi1 ao3/throw ao (throw in this sense translated in the context of words like ‘throw pillow’ or ‘throw rug,’ since it’s ‘thrown on’ to the shoulders), because it’s usually worn on the outside of a long sleeved shan or ao as an outer layer.

There are, of course, other smaller components that can determine what we call a piece of hanfu, apart from the ones we’ve already discussed and the way they’re worn. Among these include the presence of the 叉/叉/cha4/slits (side slits in a top or robe), 衣緣/衣缘/yi1 yuan2/bound hem (kind of like bias tape around the collar/sleeves of a piece), 护領/护领/hu4 ling3/protected collar (a wide piece of fabric binding the crossed collars of a lot of Ming dynasty wear), 擺/摆/bai3/swing (this is a word used for both the amount of fabric that goes into a skirt as well as the pleating or additional fabric on the sides of a robe, of which there are several types; in this case we’re referring to the latter), 细系帶/系带/xi4 dai4/ties, 腰襴/腰襕/yao1 lan2/waist piece (we’ve gone over this before in the body article, applies to the ru and a couple of other less common pieces), and some more that aren’t as commonly seen.

For example, a 道袍/道袍/dao4 pao2/Tao robe is a Ming dynasty cross collar robe, or jiaoling pao, that’s constructed with a huling and bai, specifically 内摆/内擺/nei4 bai3/inner swing, meaning the additional pleating happens on the inside, not added on the outside.

Alternatively, a 直裰/直裰/zhi2 duo1/Zhiduo robe is very similar in that it’s also a cross collar robe, but it has no bai at all. Another popular item of hanfu is the 褙子/褙子/bei4 zi0/Beizi outer garment, which is essentially a duijin changshan or parallel collar long top that has yiyuan, a bound hem, along the sleeve cuffs and the collar.

This information and way of interpreting hanfu can also be used to break down some of the less commonly seen designs that you might see appear from time to time. For example, the 唐半臂/唐半臂/tang2 ban4 bi4/Tang dynasty half arm is a piece of single-layered innerwear usually worn under a Tang style yuanlingpao or other outer layers. Looking at the picture, we can see that it’s got a very low crossed collar with a very short half sleeve or even no sleeve. It also has a contrasting colored lan, or yao lan, similar to the ru, and goes down to the knee or almost to the knee. This way we can understand how the piece is likely constructed in a more easily digestible way: it’s essentially a low cross-collar shan with a ru.

More articles in this series may come in the future, but for now, this is it, folks! I hope that you guys have fun looking at hanfu in a new way and that if you have any questions you go ahead and ask. Remember that these are just guidelines and there will always be outliers that don’t follow these rules and categories exactly; this is just an easier way to interpret the construction or pattern of hanfu and understand general trends in its design. Thanks for reading, everyone!

THE WAY ALL THE INFO YOU TAUGHT US COMES TOGETHER... thank you so so much for this guide, it's incredible!! I've learnt so much😍

thank you!😍👍

Thank you

Thank you for your hard work! I genuinely enjoyed and learned a lot the series, looking forward to reading more from you!

I want to learn how to match traditional hanfu with modern clothes so that I can wear my beautiful hanfu every day.

I don't think you need to learn. I think this is typically a situation that calls for field experimentation ^^

Congratulations on your series! it was truly great! thank you